Reclaiming Sound, One Note at a Time – My Cochlear Implant Journey

Over the past three—or even four—decades, I gradually lost my ability to hear normally. What began as the occasional missed words in a conversation or notes in music slowly turned into a daily effort to follow conversations with family and friends, and to take part in regular life. A few months ago, I decided that I did not want to continue adapting around this hearing loss. A few weeks back, I underwent cochlear implant surgery to reclaim the life that had been slipping away.

The goal of this blog is to document my journey with the cochlear implant — from the gradual fading of hearing, to the decision to act, the research and surgery, the activation and mapping process, and life with the implant today. I will share what I learned along the way, the practical aspects of the treatment, and how sound is returning to my world one note at a time. In short, this will serve both as a record of my experience and a reference for anyone curious about the process.

Before I proceed with this blog, I would like to thank the following people who have played an important role in this journey.

- My wife, who has supported me throughout my life with hearing loss — constantly adapting, communicating with patience, and standing by me during the many stressful moments when I struggled with my hearing.

- My friend and audiologist/speech therapist, Ms. Rashmi. Meeting her was the turning point that set this journey in motion. Her guidance shaped every major decision — from choosing the right doctor and audiologist to selecting the implant itself.

- Dr. Manoj and Mr. Sashidharan, whose skill and care I believe have given me a new lease on hearing and, in many ways, a new life.

- My children, who have grown up adapting to my hearing loss and have always communicated with patience and understanding.

- And finally, my friends and colleagues at work, who have supported me throughout my hearing loss. I cannot recall a single instance where anyone mocked or diminished me because of it.

As this is going to be a very long article, I have split this into various sections. You can jump to the section of interest from the below table of contents. You can use the Back To TOC link below each section to return back to this section.

Part – 1: Long Road to the Decision

My journey toward a cochlear implant didn’t start with one moment. Over decades, I lost my hearing, changed how I lived, and learned to adjust more than I realised. In this part, I look back at how sound slipped away, how I worked around the gaps, and how the idea of an implant slowly shifted from a distant option to something I knew I had to do.

When Hearing Faded

My hearing loss was not sudden. It faded slowly over several decades. Though this made life difficult, I am still thankful for the way it happened. I grew up with normal speech and communication skills, enjoyed music fully, and my brain had time to adapt as my hearing declined.

The earliest incident I remember was from my school days — a cyclist rang his bell behind me, and I continued walking, unaware, until he scolded me for blocking his way. In college, I often asked friends to repeat what they said. I sat in the first couple of rows to follow lectures clearly (I was a first-bencher for a different reason). When listening to music, I would miss notes from instruments like the violin or flute, especially in the higher octaves.

During the early years of my career as a hardware engineer, I noticed practical challenges — not hearing the office phone ring, missing the beeps from a multimeter while checking continuity on circuit boards, and relying more on visual cues than sound.

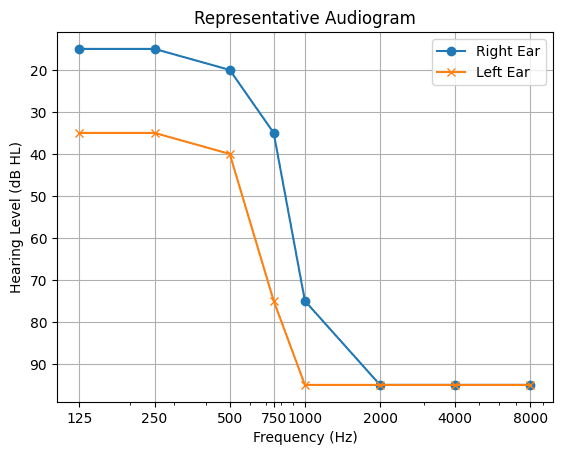

The first time I ever got my hearing tested was in IIT Mumbai in 1997, when I was 24. A friend working as a research assistant invited me to participate in a study. The audiogram showed severe loss in the 1–2 kHz range, and profound loss above 2 kHz. (I will explain audiograms in a later section.) I was advised to explore hearing aids, but was also told they might not help much for my type of loss. At that time, they were far too expensive for me anyway.

Over the next 30 years, the decline continued. Each audiogram showed more frequencies dropping out. For the last 10 years, my left ear has had no usable hearing. In the right ear, only a sliver of low-frequency hearing — below 500 Hz — remained.

Looking back, the change was never sudden. There was no single moment that marked the shift. It was a slow drift — one that I learned to live with, without fully noticing how much was fading. Only later did I realise how much energy I was spending every day just to listen.

Life With Hearing Loss

Living with gradual hearing loss is not just about sounds getting softer. It changes how you move through daily life, how you communicate, and how you experience music — something that was once effortless becomes a series of adjustments, workarounds, and choices. For me, this played out in three areas: environmental sounds, conversations, and music.

Environmental Sounds

Environmental sounds are mostly binary — either they can be heard, or they can’t. As my hearing faded, these sounds began disappearing one by one, and I learned to work around them. Below are a few examples.

I often could not hear the doorbell in hotels, so I started telling the staff to knock instead of ringing. I could not hear my phone ringing, so I began depending on a smartwatch that vibrated for calls and notifications. During bird photography trips, when others would be discussing and identifying birds by their sounds, I would not be able to hear any sounds.

On the road, as I could not hear external traffic sounds like car horns, ambulances etc., I developed a habit of constantly scanning the rear view mirros to be visually aware of traffic around me than depending on sounds.

These adjustments became routine. After a while, I stopped thinking of them as substitutes — they were simply how I lived.

Conversations

Conversations became the most draining part of daily life. Understanding speech required effort, context, and continuous lip reading. Watching television without subtitles was impossible, so closed captions became standard — for movies, shows, news, even YouTube videos.

I avoided phone calls at work as it was very difficult to follow a conversation. Email and messaging became my preferred communication channels, even for things that could have been resolved quickly over a call. In restaurants, I chose places without loud music, or asked for a quieter table. While sitting with friends or family, I would pick a seat where I could see everyone clearly, so that I could lip read.

All these adjustments helped me stay connected, but they came with a cost. Every conversation required focus, and by the end of the day, I was tired not from talking, but from listening.

Music

Music had always been an important part of my life. While in school and college, I loved listening to movie songs, western instrumental music by Ventures, Shadows, Bert Kaempfert etc., and instrumentals from Ilayaraja. But hearing loss changed how I listened and what I listened to. Over the years, several instruments began fading out. First it was high notes from the flute and violin, then almost all the notes from these instruments.

At some point, I realised I could not follow songs with female vocals anymore, especially in higher notes. I naturally shifted toward music with deeper male voices — S. P. Balasubramanyam, Jesudas and Kishore Kumar became regular choices, because I could hear them more clearly. In the last 10 years, even high pitch songs from male singers went out of my hearing.

I also liked to play the Guitar and sing. I had chosen the guitar as my instrument, partly because I enjoyed it and partly because, earlier on, I could hear every note. But when the notes on the first string — the highest in pitch — became difficult to hear, playing the guitar slowly stopped making sense. About fifteen years ago, I put it down and did not pick it up again.

Even after I stopped playing the guitar, I could still sing well. One activity that I enjoyed the most was singing Karaoke with my daughters. But in the last 5 years or so, as I could not hear my own voice in higher pitches, singing on key became a problem too, and gradually I stopped singing too.

Looking back, none of these changes came overnight. They were gradual, often subtle, and easy to ignore in the moment. But together they shaped how I lived, listened, and interacted with the world. I adapted wherever I could, sometimes without realising how much energy those adaptations required.

Choosing to Act – Decision to Get a Cochlear Implant

There was no single moment when I decided I needed a cochlear implant. The decision formed slowly over many years, as both my hearing and the available technology changed.

I first heard about cochlear implants about fifteen years ago. My company had arranged for my hearing to be tested at Stanford, and after the evaluations, the ENT surgeon told me that I was a candidate for an implant, and that he was even surprised how I was living a normal life with this amount of hearing loss. At that time, I still had enough residual hearing to manage daily life, and cochlear implant surgery was not as effective at preserving that remaining hearing as it is today. The risks mentioned in the consent forms — especially the possibility of facial nerve injury and paralysis — stayed with me. I was not ready to take that step. But I told myself that if my hearing declined further, and if the technology improved, I would reconsider the option in ten or twenty years.

So instead, I got a pair of hearing aids. They could not do much for frequencies above 2 kHz, but they still helped enough for the next four or five years to make daily life manageable.

The next push came around 2020, during a conversation with my friend Rashmi, an audiologist and speech therapist in Bangalore, whom I had met through a car drive and meet. She could see the effort I was putting into communication and told me that I should start thinking seriously about cochlear implantation. Even then, I felt the risks outweighed the benefits. I also told her that I would probably wait until I crossed fifty, hoping that by then I would feel more prepared.

Over the last couple of years, my residual hearing declined sharply. I found myself exhausted from listening and struggling even with all the adaptations I had put in place. In September last year, I met Rashmi again at another drive meet. This time, I told her I was ready for the cochlear implant and asked her to guide me through the process.

During this meeting, Rashmi spent time explaining what I should realistically expect from the implant. A cochlear implant works best when done soon after the hearing loss, while the brain still remembers what sound feels like. In those cases, the brain can adapt quickly, and speech understanding comes sooner.

In my case, the loss had stretched across decades. Many frequencies had faded away slowly over 10 to 30 years. Because of that, the outcome could not be predicted with confidence. The implant would give me access to sound as soon as it was activated, but understanding speech — especially without lip reading — would take time. She told me that six months to a year of regular speech therapy might be needed to retrain the brain to interpret the new signals, and that the effort would have to come from me. There were no guarantees — only possibilities shaped by patience and hard work.

She also reassured me that even if the result wasn’t perfect, any improvement would make life easier than where I was at that moment.

I also took this opportunity to discuss my concerns on the risk factors. Some of the risk factors that I was concerned about were the injury to the facial nerve during surgery (the facial nerve runs very close to the site where the surgeon drills a hole in the bone to insert the electrode array), and the safety of general anaesthetic. Rashmi clarified that though my concerns were justified, the technology today has improved a lot that the probability of anything going wrong is very remote, and the rewards far outweigh the results.

Choosing the Surgeon and Evaluation

Rashmi told me that the first step was to choose a surgeon and go through a thorough evaluation. Before anything else, we had to confirm two things — how much of my hearing I had actually lost, and whether the inner ear was physically healthy enough to support an implant. This meant an audiogram to measure hearing levels, and MRI and CT scans to check the condition of the cochlea and the auditory nerves. Only after the surgeon reviewed everything and confirmed that an implant was viable could we move forward.

I read a lot about famous surgeons in cochlear implant. I looked for a surgeon who had good experience and at the same time accessible to me from Coimbatore. I finally chose Dr. Manoj from Calicut. He has performed close to 2,000 cochlear implant surgeries and is considered one of the leading surgeons in India in this field. Calicut was also about a five-hour drive from Coimbatore, which made follow-up visits easier.

I called the clinic and scheduled an evaluation. In mid-November, I drove to Calicut for my first visit.

I first met Mr. Sashidharan, who carried out several tests — a full audiogram, speech understanding tests, and trials with a few high-powered hearing aids to see if they still offered any benefit. The hearing aids didn’t make much difference, and I told him I was ready to consider an implant.

Next, I met Dr. Manoj. After looking at my test results, he asked me to get MRI and CT scans of my inner ear so he could study the anatomy in detail. I got the scans done the same day. When I returned the next morning, he reviewed them carefully and confirmed that my cochlea and auditory nerves were physically fine. We could proceed with the implant.

I then met Mr. Sashidharan again for counselling. His guidance echoed what Rashmi had told me — with my long period of auditory deprivation, predicting the outcome was difficult even though the anatomy was normal. He asked me to set my expectations realistically, perhaps aiming for around 30–35% speech understanding initially, with the understanding that progress would depend on consistent therapy and my own effort. But even that level of improvement, he said, could make daily life much easier and reduce the constant listening fatigue I had been living with.

He also walked me through the different implant options available from Cochlear, Med-El, and Advanced Bionics, and asked me to read about each one before deciding. The choice will have to be purely mine.

It was clear that the evaluation wasn’t just about tests — it was about aligning expectations, understanding the journey ahead, and making informed choices.

Part 2: Anatomy of Hearing, Hearing Loss, and Cochlear Implants

Before choosing a device, I had to go back to the basics: how natural hearing works, what exactly sensorineural hearing loss is, and how that shows up on an audiogram, and how a cochlear implant fixes this.

How the Ear Works

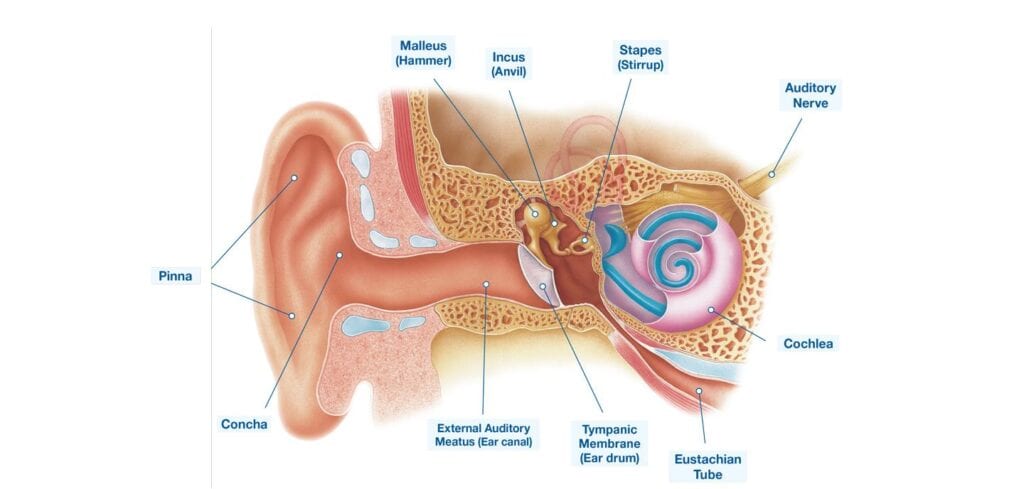

Image Credit and Source: https://www.beltone.com/en-us/articles/how-our-ears-hear

The ear is divided into three parts – the outer ear, middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear collects sound waves and funnels them through the ear canal to the eardrum, where vibrations start. These vibrations pass through the three tiny bones of the middle ear — the malleus, incus, and stapes — which amplify and transmit them into the inner ear.

Inside the inner ear sits the cochlea, a fluid-filled structure shaped like a small spiral. When the stapes pushes against the oval window of the cochlea, it creates ripples in the fluid. These ripples bend thousands of tiny hair cells arranged along the cochlea’s length. Each hair cell responds to a specific frequency — high near the wider end, and low tones near the narrow tip.

As hair cells move, they convert mechanical vibration into electrical signals. These signals travel through the auditory nerve and finally reach the auditory cortex in the brain, where sound becomes meaningful — speech, music, the call of a bird, or the hum of traffic. Below video shows how the auditory system works.

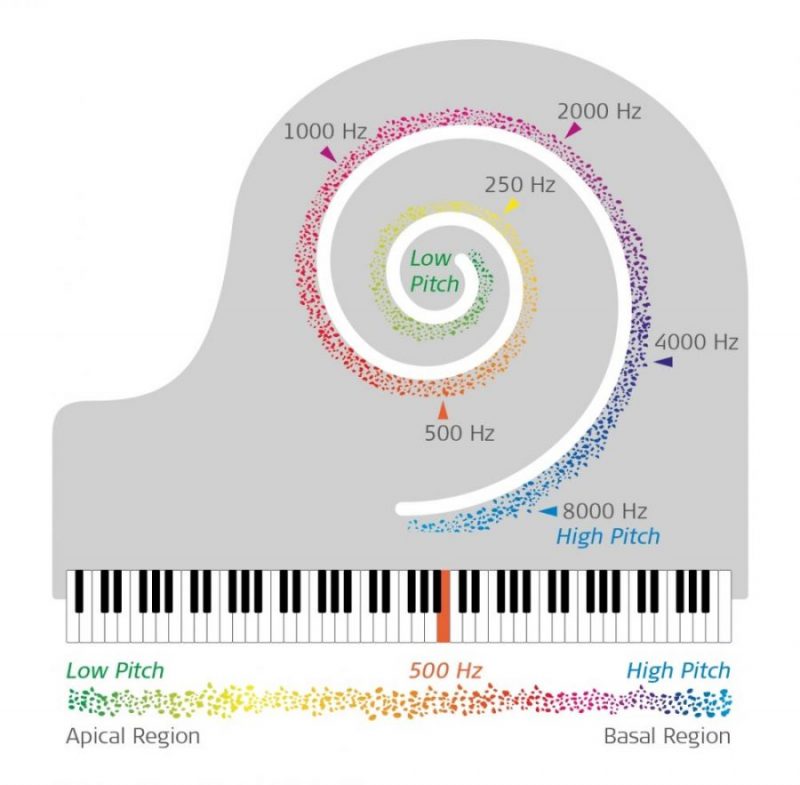

The Cochlea and Frequency Mapping

The cochlea does more than detect sound; it separates it by pitch. This ability comes from its tonotopic organisation, where different frequencies activate different regions:

- High frequencies (like birdsong or consonants such as s, t, f) are detected at the base of the cochlea.

- Mid-range frequencies (most everyday speech sounds) sit along the middle region.

- Low frequencies (such as drums or vowel sounds) reach the apical end, deep inside the spiral.

The picture below shows a tonotopic map of a cochlea.

Image credit/source: Med-El

When the delicate hair cells in the cochlea deteriorate, their ability to convert vibrations into electrical signals weakens, and this is known as sensorineural hearing loss. It’s the most common form of hearing loss and the one that applies to my case.

In sensorineural loss, the pathway to the brain remains intact, but the signal itself becomes faint, or is lost, especially in the higher frequencies that carry clarity in speech. This is why voices may seem loud enough yet unclear, and why consonants — s, t, f, sh, ch — fade first, long before deeper sounds like vowels or background noise.

There are other forms of hearing loss — conductive, where sound struggles to reach the inner ear due to issues in the outer or middle ear. But in those cases amplification or medical treatment often helps.

With sensorineural loss, however, volume alone isn’t the problem. The issue is that damaged hair cells cannot be repaired or replaced naturally, and the information they once carried never makes it to the brain. As the loss deepens over time, understanding speech becomes harder, especially in noise, and listening requires constant effort.

The Audiogram

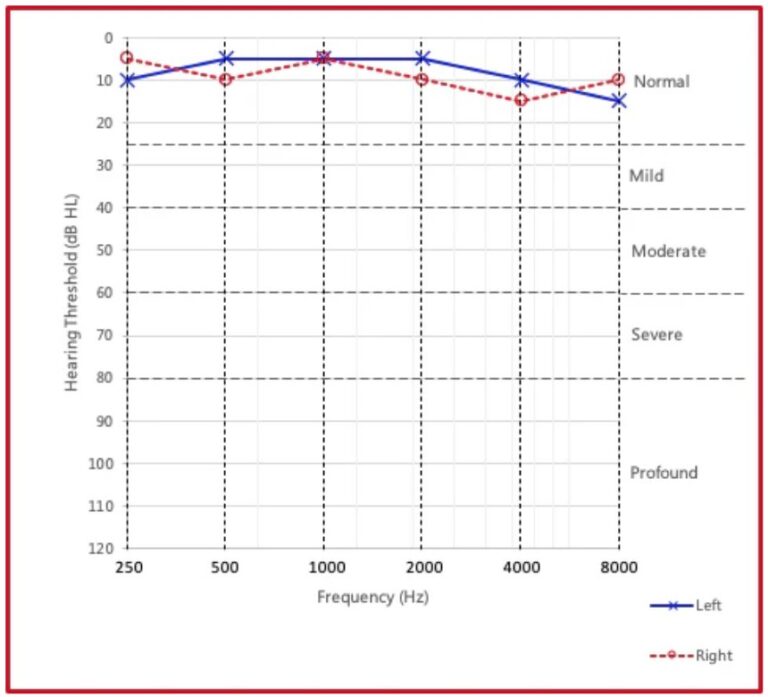

An audiogram is the standard chart used to measure and represent hearing ability. On an audiogram, the X axis represents frequency, measured in Hertz (Hz), and the vertical axis represents the loudness level one can hear, and is measured in decibels (dB).

To create the audiogram, a pair of headphones are placed over the ears of the subject, and a series of test tones at various frequencies and loudness are played through the headphones. For each frequency, the loudness of the tone at which the subject is able to hear is marked.

Below picture shows the audiogram of a healthy adult with normal hearing. All the frequencies are in the 0 to 15dB range. As one loses normal hearing, depending on the loudness one can hear, the loss is classified into medium, severe and profound.

Image credit/source: Audiogram

Below is the audiogram approximating my condition when I was tested in Stanford 15 years back. I don’t have the actual report, and have created this from my memory. At that time I remember I had good residual hearing in the frequencies up to 500Hz, which was enough to manage with lip reading. My left ear was worse than the right.

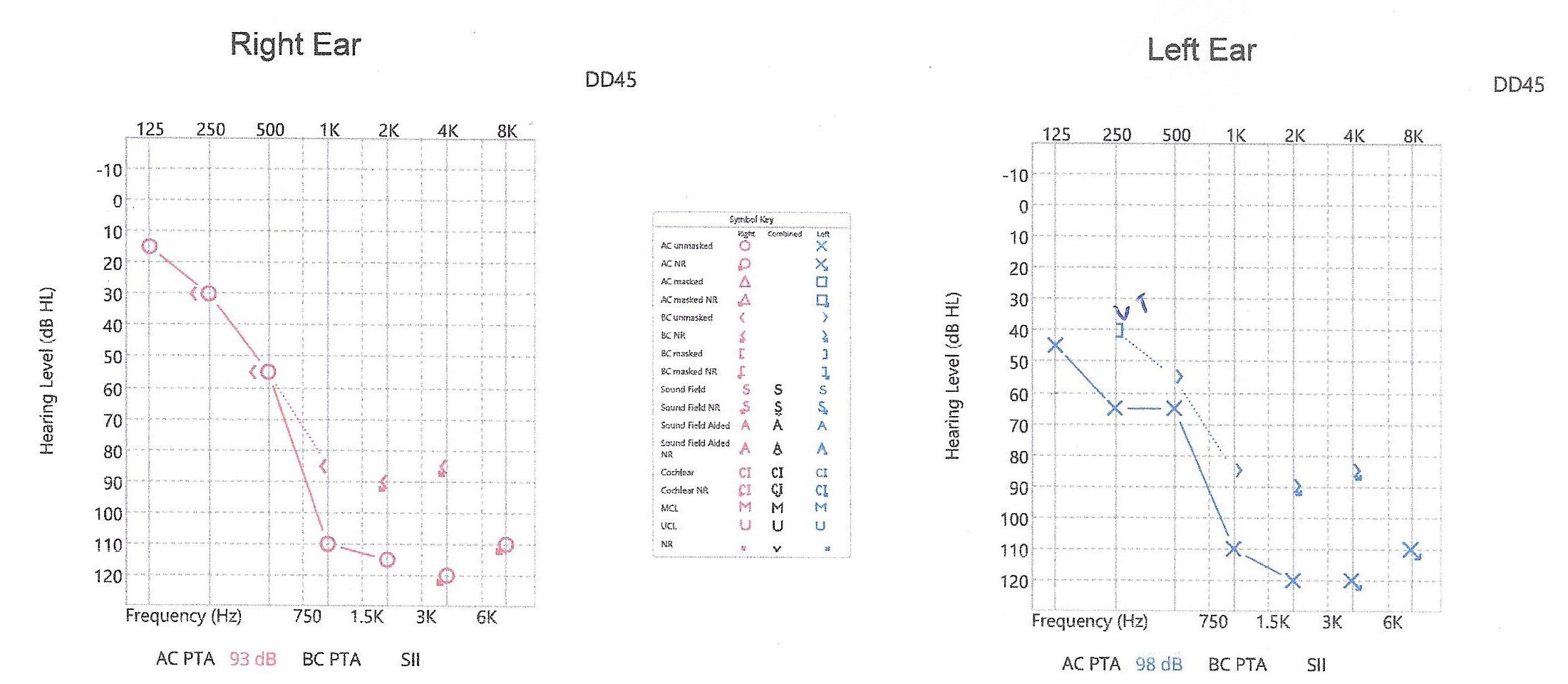

Below is the audiogram from the recent test done at Dr. Manoj’s clinic during the evaluation. There was almost no residual hearing left in the left ear, and only 125Hz remained normal in the right ear. This should give an idea of how difficult it was for me to manage conversations. This also shows why hearing aids are useless. Hearing aids can’t do anything for the frequencies that are below 80 or 90dB.

How Cochlear Implant Works

Now that we know how hearing works, what sensorineural hearing is, and my audiogram to understand the severity of my hearing loss that hearing aids can’t fix, let us have a look at how a cochlear implant works, and how this solves the problem. A cochlear implant is divided into two parts – the internal part which is called the implant, and the external part, which is called the speech processor.

The Internal Implant

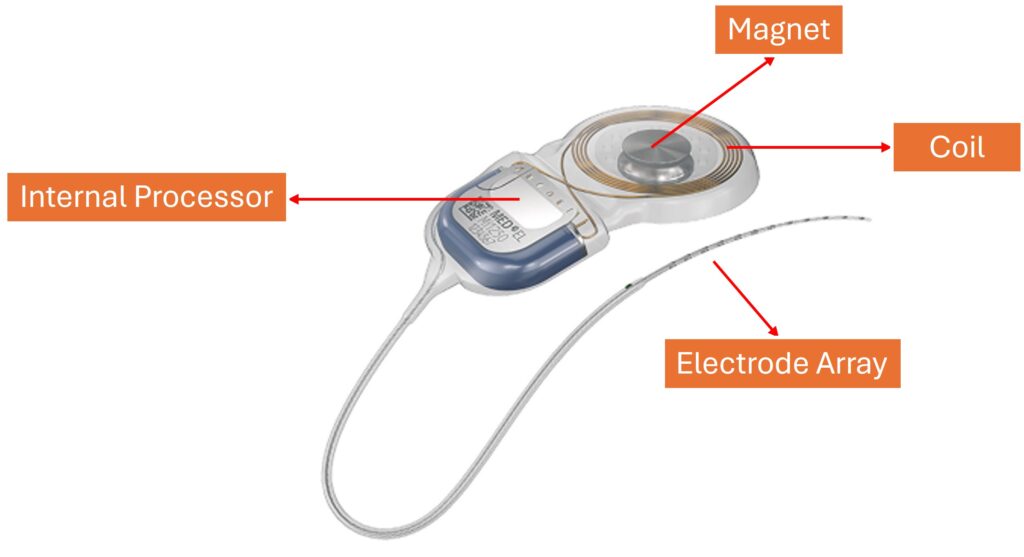

The implant is surgically placed inside the head, behind the ear, between the skin and the skull. A pathway is made through the bone to visualize the round window of the cochlea and the electrode is inserted through the round window. Below picture shows the implant.

Image source: Med-El

The magnet is used to magnetically attach and hold the external processor outside the head. The coil is used to wirelessly receive power and the audio signals from the speech processor. The internal processor decodes the signals received from the speech processor and drives the electrodes in the electrode array. The electrode array is what sits inside the cochlea and transmits the electrical signals from the processor to the auditory nerve.

The External Speech Processor

The speech processor sits outside the head. It receives sound from external world, processes this sound and transmits this information wirelessly to the internal processor. It also transmits power to the internal processor.

There are two types of external processors based on the form factor – Behind the Ear (BTE), and Off the Ear (OTE). Each has its own pros and cons. The BTE is more rugged, can have bigger battery with longer battery life and can stay in place even with lots of physical movement, but is visible more prominently. The OTE is more discrete, easy to fix and remove, but has battery life limitations, and has to be secured with bands or other means during physical activities.

Below video shows how a cochlear implant works.

Part 3: Choosing the Implant

Once I understood the details of how hearing works, what sensorineural hearing loss is, and how a cochlear implant solves this, I was ready to choose the implant. Unlike hearing aids, this is not something you can change easily later. The internal implant is meant to last a lifetime, so this choice needed careful thought.

In this part, I will briefly walk through the selection process — clearly defining my requirements and priorities, the three major manufacturers, the options from them, important strengths (and weaknesses) of these manufacturers, and how I finally chose the device I now carry inside my inner ear.

My Expectations from the Implant

My main motivation for choosing a cochlear implant was music. I wanted to hear the flute and violin again, enjoy the songs I used to listen to, and eventually get back to playing the guitar and learn some new instruments too. But from several user reviews and comments, I understood that I need to keep my expectations under control.

I also wanted better access to everyday sounds — the calling bell at home, an approaching ambulance, sound of approaching vehicles when I walking or running on the road, the sound of birds on the bird photography trips, the beeps from the reverse parking sensor in my car, and many more.

With conversations, my goal was clarity without fatigue. I wanted to follow speech more naturally and participate in group discussions without depending so much on lip reading, or watch movies without depending on subtitles.

Analyzing the Options

Once I had my priorities clear, I spent the next few days reading about cochlear implant technologies. I had three companies to choose from. I went through technical specifications, manufacturer literature, and user experiences shared on forums and groups on Reddit and Facebook.

While analysing the options, these were the key parameters I considered.

Electrode length: This is one of the most important factors influencing sound quality. As discussed in the previous section, different regions of the cochlea respond to different frequency ranges. A longer electrode provides greater cochlear coverage, allowing access to a wider range of frequencies and, potentially, a more natural perception of sound.

Number of electrodes in the array: The cochlea contains thousands of hair cells organised across many frequency channels, enabling fine pitch discrimination. This is especially important in music, where the brain needs to distinguish between closely spaced notes, such as A and A♯. In contrast, a cochlear implant has only a limited number of physical electrodes. To compensate, manufacturers use advanced signal processing techniques to create virtual channels, which help improve pitch resolution.

Signal processing strategies: Each manufacturer takes a slightly different approach to signal processing. Some prioritise speech clarity and understanding speech in noisy environments, while others focus more on delivering a natural sound quality.

MRI compatibility: MRI compatibility is an important practical consideration. Since the internal implant contains a magnet, MRI scans can create strong forces that may cause discomfort or pain. Modern implants address this by using self-aligning magnets that rotate and align with the MRI’s magnetic field, reducing force significantly. Implants are generally classified as either non-MRI compatible or MRI compatible up to 1.5 or 3.0 Tesla.

External processor form factor: As mentioned earlier, external processors come in two main form factors: Behind-the-Ear (BTE) and Off-the-Ear (OTE). Some manufacturers offer both options, while others focus on only one.

Digital connectivity: In today’s world, wireless connectivity is essential. Cochlear implants allow direct streaming of phone calls, music, and other audio to the processor. Some manufacturers offer more seamless Bluetooth integration than others.

Cochlear

Cochlear, a company based in Australia, is the most widely used cochlear implant manufacturer globally, with a market share of around 60%. They are known for their focus on speech understanding, strong digital connectivity, and overall reliability.

- Pros

- With 22 physical electrodes, they offer the highest electrode count among the three manufacturers

- Availability of both BTE and OTE external processors

- Strong speech recognition performance, especially in noisy environments

- Very good digital streaming and connectivity

- High level of trust among surgeons and a long track record of reliability

- Points to Consider

- Shorter electrode arrays (18–25 mm) that reach only the mid regions of the cochlea (which is excellent for speech perception though)

- Sound often described as tinny or metallic (which most users report goes away after a few months, due to brain adaptation)

From user feedback from forums, the most common reason why people chose Cochlear was for their excellent speech performance in noisy environments and their connectivity options.

Advanced Bionics (AB)

Advanced Bionics is a company based in the USA. One of their key strengths lies in connectivity and advanced signal processing, supported by their association with Phonak hearing aids. They use a technique called current steering, where two adjacent electrodes are stimulated simultaneously to create virtual channels between them.

- Pros

- Multi-axis magnets that allow MRI scans without restrictions on head orientation

- Current steering technology to create 120 virtual channels between electrodes

- Strong connectivity ecosystem

- Advanced signal processing strategies

- Hands-free calling support

- T-Mic design, where the microphone sits at the entrance of the ear, improving sound localisation and reducing wind noise

- Points to Consider

- Shorter electrode arrays (18–25 mm), reaching only the middle of the cochlea (which again provides excellent speech performance)

- Only BTE processors are available; no OTE option

Most of the users praised AB for their connectivity, current steering technique and their seamless integration with hearing aids from Phonak.

Med-El

Med-El is a company based in Austria, with a strong focus on natural sound and music perception. They achieve this primarily through electrode arrays that provide deeper cochlear coverage. Med-El offers the widest range of electrode lengths, allowing better matching to individual cochlear anatomy. They use dedicated software to measure cochlear length and select the most appropriate electrode array for maximum coverage.

They also use a technology called Fine Hearing, which closely mimics how the natural cochlea processes sound. Higher frequencies (above ~1 kHz) are encoded using place coding, where pitch is determined by the location of stimulation along the cochlea. Lower frequencies are encoded using temporal coding, which preserves the timing of sound waves. In addition, Med-El supports Anatomy-Based Fitting (ABF), where post-operative CT scans are used to determine the exact electrode positions and map frequencies accordingly.

- Pros

- Widest range of electrode array lengths (18–34 mm)

- Soft, flexible electrodes designed to preserve residual hearing (not applicable in my case)

- Fine Hearing technology aimed at producing a more natural sound

- Anatomy-Based Fitting (ABF) for precise frequency mapping

- 256 virtual channels though they have only 12 physical electrodes

- Points to Consider

- Limited native connectivity; Bluetooth streaming requires an intermediate device called AudioLink

- Lowest number of physical electrodes (12), compared to 22 for Cochlear and 16 for Advanced Bionics (which is compensaged by the 256 virtual channels)

Most of the user feedback I found about Med-El consistently highlighted how close the sound felt to natural hearing. I also came across a significant amount of literature and video material from Med-El focusing specifically on music perception and how their design choices support it.

My Choice – Med-El Synchrono Implant with Rondo 3 Processor

After comparing the technical specifications, strengths and weaknesses, and real-world user experiences of all three manufacturers, the choice became clear for me. Med-El consistently prioritised natural sound and music perception—both of which were central to what I wanted from an implant. Given my background with music and my long-term hearing loss, this alignment mattered more to me than speech optimisation.

While connectivity and ecosystem features were stronger in some of the other systems, I felt that Med-El’s approach to electrode design, cochlear coverage, and sound encoding offered the best chance of restoring a sound quality that felt natural rather than artificial. Based on these factors, I decided to go with the Med-El Synchrony implant paired with the RONDO 3 off-the-ear processor.

An important note on implant selection:

The choice of implant and electrode is not purely a personal or technical preference—it is primarily determined by the physical condition of the cochlea. During evaluation, the surgeon assesses whether the cochlea is healthy and free from ossification (where soft tissue hardens into bone), which can limit electrode insertion.

If the cochlea is healthy and unobstructed, a longer and softer electrode can be inserted, allowing deeper cochlear coverage and better access to lower frequencies. If there is ossification or structural limitation, the surgeon may need to choose a shorter and stiffer electrode to ensure safe insertion.

In my case, the imaging showed that my cochlea was healthy, with no ossification. Based on this, the surgeon recommended a long, soft electrode array, which also helps preserve any residual hearing. This made Med-El an even more natural fit for my situation.

I would like mention one reassuring observation from my research: regardless of the manufacturer, model, or specific strengths and limitations, most users seemed generally happy with their cochlear implants and the improvement they brought to daily life. So, my selection of Med-El is based on my own priorities and my test results. This article should not be considered as a medical advice.

Depending on an individual’s priorities, the choice between the implants can be different.

Cost of the Implant and Surgery

The cost of Synchrono 2 + Rondo 3 from Med-El cost 15.25 lakhs. The surgery costed 2.25 lakhs. Including other expenses for the MRI, CT scans, other tests etc., the total cost was around 18 lakhs.

The cost of the implant and processor greatly varies based on various factors like MRI compatibility, BTE or OTE, and manufacturer. The implants without MRI compatibility cost 4 to 5 lakhs less than the implants with MRI compatibility. Between the three manufacturers, I found the cost ranging from 6 lakhs to 18 lakhs for the implant and the processor.

Note: In USA and other Europian countries, cochlear implant is covered by insurance. But in India, insurance does not cover the cost of cochlear implant.

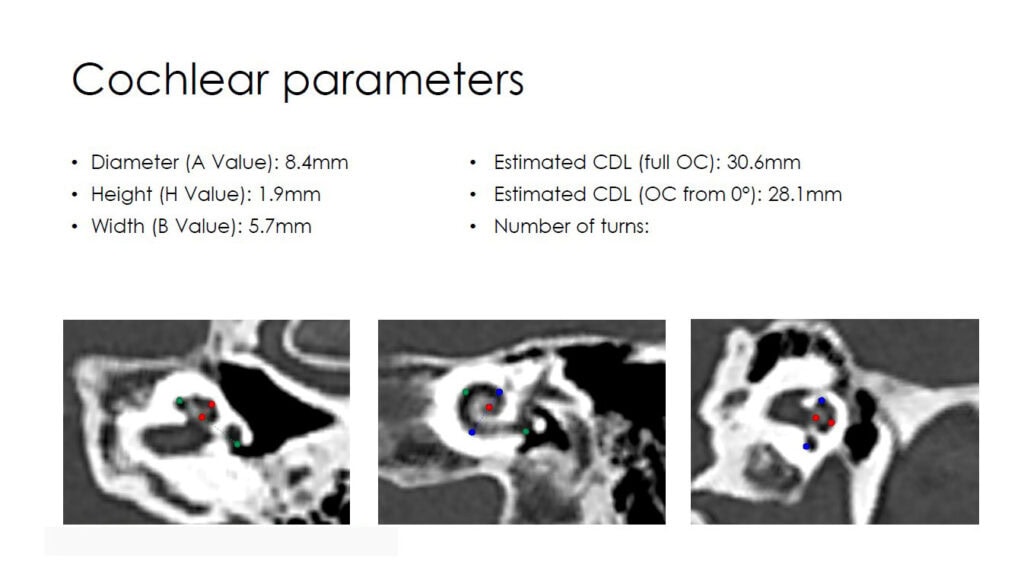

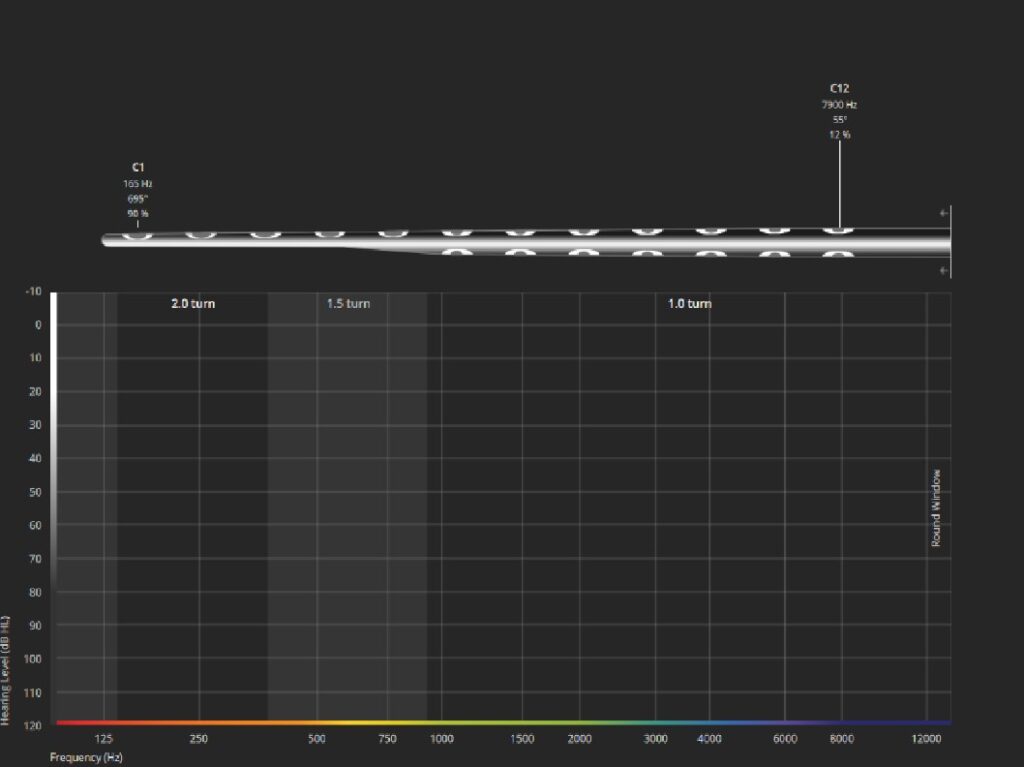

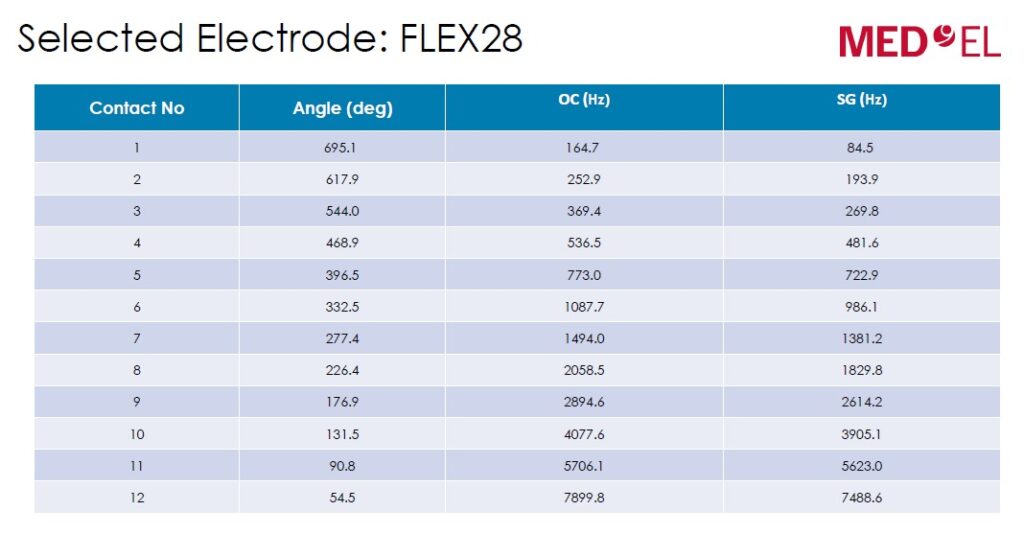

Otoplan – Choosing the Length of Electrode Array

Once I decided to go with Med-El, I informed the audiologist, Mr. Sashidharan, about my choice and the reasons behind it. He confirmed that, given my requirements, this was a good fit. The next step was to select the appropriate electrode array.

Med-El offers a range of soft electrodes under the Flex series, with lengths ranging from 18 mm to 34 mm. Mr. Sashidharan forwarded my MRI and CT scans to the Med-El team, who analysed them using a software tool called Otoplan to determine the most suitable electrode.

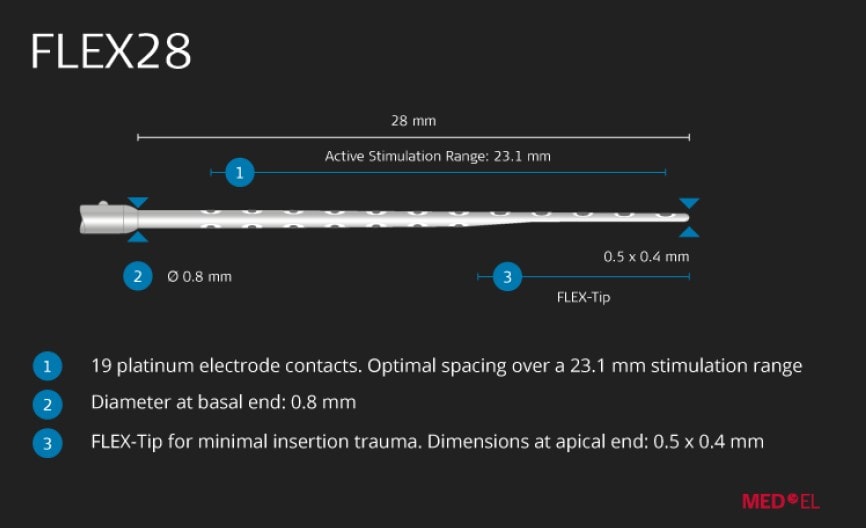

The measured length of my left cochlea was 30.5 mm. Based on this, the two closest electrode options were the Flex28 (28 mm) and the FlexSoft (31.5 mm). Since the FlexSoft is longer than my cochlea, it would not allow a full insertion. As a result, the Flex28 was recommended.

Below are some screenshots from the Otoplan analysis. The software provides a simulated projection of how the electrode array would be positioned inside the cochlea, along with the corresponding centre frequency assigned to each electrode location. This is only an approximation—the actual placement can vary during surgery, and the exact electrode positions are later determined using a post-operative CT scan.

Part 4: Surgery, Activation of the Implant, and Recovery

Pre-Surgery Tests

Once we finalized the implant, electrode, and processor, I completed the payment for the implant and surgery, and the hospital placed the order with MED-EL, and a tentative date in mid-December was fixed for the surgery.

The surgery department sent me a checklist with a list of tests to be done and a vaccination to be taken. Below is the list.

- Sugar

- Lipid profile

- Electrolytes

- Echo cardiogram and fitness certificate from cardiologist

- HIV

- HCV and Liver function test

- Polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine

I completed all the tests, and everything turned out to be normal. In the first week of December, I received confirmation from the clinic that the implant had arrived and that the surgery would go as planned in the second week..

Surgery

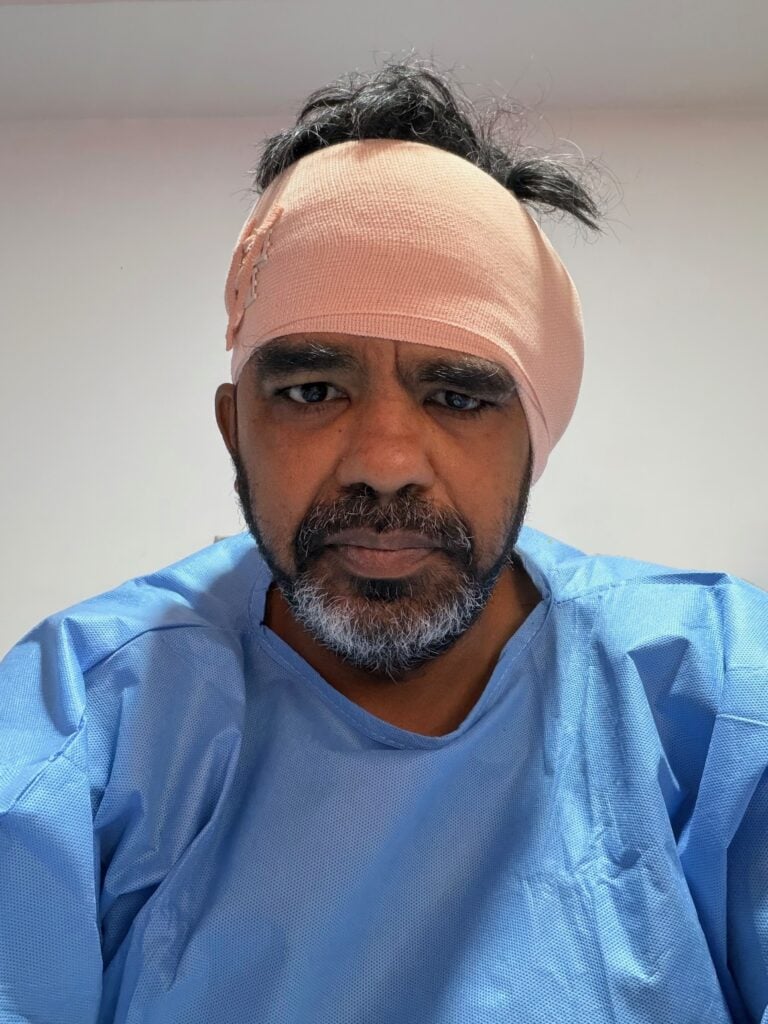

I checked in at Dr. Manoj’s ENT clinic one day before the surgery, in the evening. The next day, at 7:30 in the morning, I was taken to the ICU, where they performed some routine tests like blood pressure, blood oxygen levels, and a few allergy tests (possibly for the anaesthesia). They then put me on an IV drip. A picture of me just before being taken to the ICU.

At 8:30, they wheeled me into the OR. I felt something cold going into the IV line, and the last thing I remember is the overhead lights in the operating room.

When I woke up, I found myself back in the ICU, and the time was 12:45. So I was out for about four hours and fifteen minutes. By 1:00, the anaesthesia had cleared, and I was able to sit up. They explained that the surgery was a success and that the actual procedure had taken about one and a half hours. At 2:00, I was moved to my room. Except for a couple of instances of post-anaesthetic dizziness, I felt completely fine.

During the surgery, after Dr. Manoj inserted the electrode array into the cochlea, Mr. Sashidharan performed basic diagnostic tests and found that all the electrodes were working fine. Something called ECAP (Electrically Elicited Compound Action Potential, that measures feedback from the auditory nerves) was also good for all the electrodes. Dr. Manoj noted in his surgical notes that the electrode insertion was full length. All of these were very promising results. A post surgery picture back in the room.

Activation of the Implant

From various user experiences that I had read, implants are usually activated two to three weeks after surgery, once the incision has healed. Surprisingly, Mr. Sashidharan told me that he would activate the implant the very next day after surgery. This was a pleasant surprise, as it avoided the long and tense wait to know whether the implant was working properly.

As promised, the day after surgery, Dr. Manoj removed the dressing over the surgical site. I then went to the audiology department, where Mr. Sashidharan connected a coil to my head and ran through several measurements. After this he placed the speech processor over the internal implant and programmed the device. I then heard a series of sounds, from low to high frequency, as each electrode was activated.

The first test passed, which meant that all electrodes were functioning properly. Next, he set the level on each electrode to a value that I could tolerate. This turned out to be about 50% on all electrodes. He then turned on all the electrodes simultaneously.

He spoke vowel and consonant sounds from my side and asked me to repeat them. I was able to identify most of the sounds correctly. He then asked a series of questions while shielding his mouth. Initially, I could not understand the sentences, as my brain needed some context. He then uncovered his mouth and asked, “What is your name?”, allowing me to lip-read. After this, he again shielded his mouth and asked questions like “How old are you?” and “What are your hobbies?” I was able to understand the words and answer most of the questions. He was speaking very softly throughout.

This was a very emotional moment. Both my wife and I had tears of joy.

Even Mr. Sashidharan was visibly surprised. He told us that on the day of activation, people like me with long period of auditory deprivation hear mostly sounds and noise,, and it usually takes time and auditory training before they start recognising words and sentences. He said it was very promising that I was able to recognise words and sentences (with context) on the very first day of activation. I still could not follow single words spoken without context. That will take time and auditory training. A couple of pictures from the activation session.

Post activation, I was discharged from the clinic, and my wife and I took a cab back home.

Recovery

Recovery was quite smooth. I was prescribed painkillers, antibiotics, and steroids for a week after surgery. During this first week, I stayed home and rested completely. I did not experience any major adverse symptoms. The pain was very mild and subsided within a few days.

The only noticeable symptom was a slight metallic taste on the left side of my tongue, which resolved within a week. During my research phase, I had learned that this is a common and temporary side effect for many patients, so it was not a cause for concern.

One thing that surprised me was how small the surgical incision was. The incision behind the ear was only about 40 mm, covered by a very small dressing. The pictures I have seen in the internet usually showed an incision covering the full length of the ear. Dr. Manoj performed a round window insertion, which is a less invasive approach compared to older techniques, and this likely contributed to the minimal incision size. Seeing how discreet the surgical site was made the recovery feel much less intimidating. A photo of the dressing behind the ear is shown below.

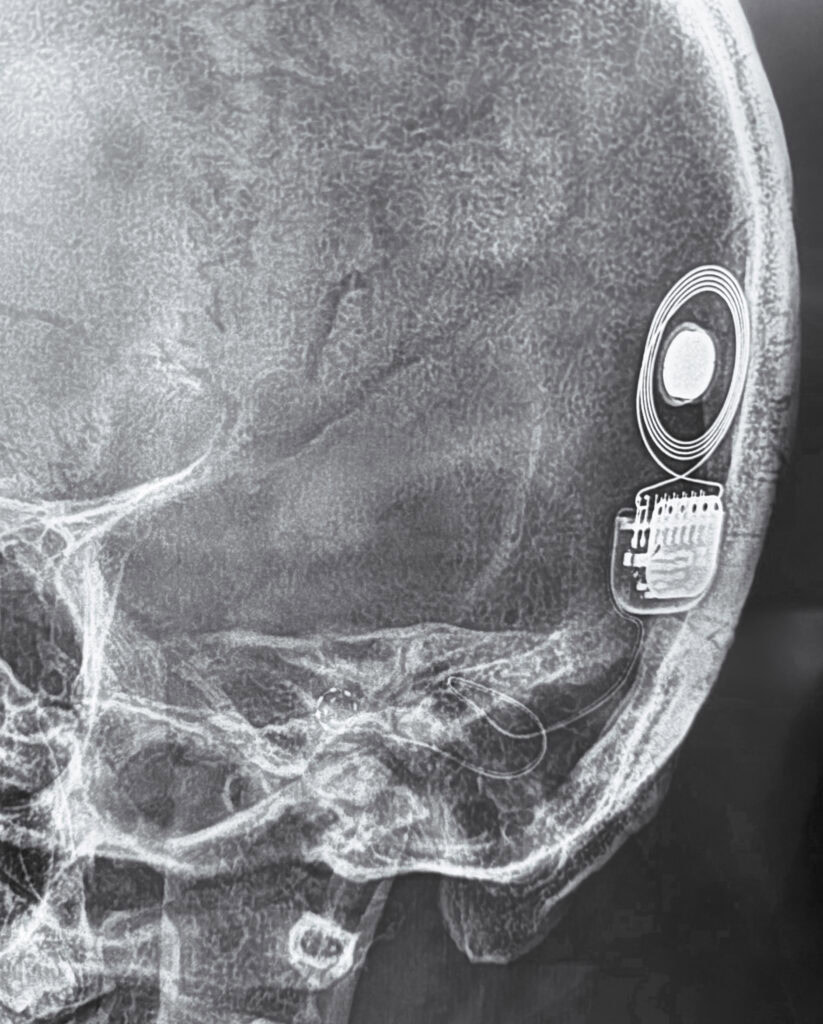

Below is a picture of post-op XRay showing how the implant is placed inside my head. Notice the looped wire that ends in a spiral inside the cochlea. 12 electrodes can be counted inside the spiral.

About a week after surgery, I resumed my morning walks. I am usually physically active, with two to three runs and a couple of strength training sessions each week. However, since strenuous activities need to be avoided for at least six to eight weeks to allow proper internal healing, I have decided to limit my physical activity to walking during this period.

Part 5: Life with the Implant – Beginning of a New Journey

In this section, I will capture my first experiences of life with a cochlear implant after activation. These initial weeks have been a period of adjustment rather than instant transformation — getting used to wearing the processor, noticing how everyday sounds reappear, how music feels, how conversations feel, and slowly learning how my brain interprets them. It feels like a new beginning, a fresh start on a listening journey that will continue to evolve with patience and practice.

The Processor

The RONDO 3 processor has been easy to live with so far. My routine is to place it on the wireless charger before going to bed and wear it first thing in the morning. The processor attaches magnetically to the head, and a safety tether prevents it from falling if it ever detaches. Without the tether, it would be easy to forget that the processor is even there.

Battery life has been more than adequate. I usually put the processor on at around 5:00 AM, and by the time I place it back on the charger at around 9:30 PM, there is typically about 20% charge remaining, with roughly three hours of estimated usage left. At the moment, the electrode levels are set to around 50%, and I have adjusted the overall gain to 75% of that using the phone app. As the gain levels increase over the next few mapping sessions, the battery life may reduce slightly, but I am hopeful it will still last a full day.

Below are a few pictures of the processor.

Reclaiming Sound

Earlier in this story, I described how I lost access to sound — environmental, speech, and music. In this section, I return to those same areas, but from the other side of the journey. What follows is my experience of how these sounds are coming back into my life, and how they feel now through the cochlear implant, as my brain begins to interpret this new way of hearing..

Environmental

Environmental sounds, which I had earlier described as binary in nature, have simply turned on. Whether it’s the microwave buzzer, an ambulance on the road, the chattering of birds, or the trilling of insects during my walks, I am now hearing sounds everywhere around me. Below are some of the sounds I am hearing either for the first time in my life, or again after several decades.

At home: the microwave buzzer, the calling bell, ringing phones, my wife and children talking or laughing in another room, the pressure cooker whistle, coffee dripping in the coffee machine, water boiling in the kettle, and many more.

While driving: beeps from the parking sensors, horns from other vehicles on the road (earlier, I could hear only the loudest ones), ambulance sirens, wind noise, road noise, and engine sounds.

During my walks: conversations of people approaching from a distance, different bird calls, trilling insects, barking dogs, the crowing of a rooster, and the sound of approaching vehicles.

This has given me a much greater sense of environmental awareness and has made life easier with sounds like calling bells and phone rings, more enjoyable with sounds like birds, and safer with sounds like approaching traffic. Many friends jokingly tell me, “Welcome to the noisy world.” While there is definitely more noise around, at least so far, all the sounds that others might find bothersome haven’t troubled me — perhaps because of how much I have gained in return.

Speech

When it comes to speech, I am now able to communicate with my wife, children, and close friends without needing to read lips. However, I still struggle to follow conversations when the context is not already known. I think my brain is still relying on its old habit of reconstructing words using context. Even so, communication at home has become largely stress-free.

What still remains difficult is understanding speech in noisy environments. In places like hotels or restaurants with a lot of background noise, I am not yet able to follow conversations reliably. While watching TV, I can make out roughly 30–40% of the dialogue, but I still depend heavily on closed captions. I am also not yet comfortable talking on the phone using speaker mode.

I believe speech understanding is an area that will require sustained therapy and consistent effort over the coming months.

Music

The following week, I took out my acoustic and electric guitars, which had been stored away in the attic for almost fifteen years. I restrung them, tuned them up, and was overjoyed to hear the last fret on the first string again. That was another moment filled with tears of joy.

That said, there are still challenges that need to be addressed. Pitch identification and discrimination are not yet very accurate. When I listen with both ears, the pitch mismatch between my natural hearing and the implanted ear means that several notes sound similar when heard in isolation. When playing a melody, I can still recognise the tune, but even if I play a wrong note — for example, A♯ instead of A — the melody may still sound acceptable to me.

Earlier, I used to play songs entirely by ear and could easily identify mistakes. I had only a high-level understanding of music theory, mainly major and minor scales. I can no longer rely on that approach. I now need to change how I play — by understanding the exact scale a song is composed in, knowing the correct notes to play, and consciously avoiding wrong ones. This, in itself, feels like a completely new journey.

While listening to music, tracks with fewer instruments sound cleaner and more pleasant. Songs with a dense mix of instruments can sound confusing. With male voices that fall within the residual hearing range of my right ear, I often perceive two voices — the one in my left ear sounds higher in pitch by roughly two semitones. I jokingly told my friends that S. P. Balasubrahmanyam is singing in A minor in my right ear and B minor in my left. When I sing along, I end up hearing four voices!

From user experiences shared on forums, this phase is expected in the early stages, and music appreciation typically improves over time. In general, music becomes significantly more enjoyable over a period of six months to a year. The pitch mismatch between the natural ear (with residual hearing) and the implanted ear is also expected, and audiologists usually address this by fine-tuning the frequency mapping to better align both ears.

The Road Ahead – Next Steps

As I write this, it has been three weeks since my surgery and activation. Everything I have shared so far reflects my experience with the basic, default tuning done during the initial activation.

The next step is fine-tuning the frequency mapping of the electrodes. Typically, audiologists perform a series of mapping sessions over the first six months to a year. I have already completed a post-operative CT scan and shared it with Mr. Sashidharan. During the first follow-up session, scheduled for next week, he will perform an anatomy-based fitting, where the electrode frequencies will be remapped based on their exact positions inside my cochlea. From my research, I also understand that Med-El offers different mapping profiles optimised for speech, music, and other listening scenarios, which can be enabled using the mobile app. I am very much looking forward to these sessions and the improvements they are expected to bring.

Another important step ahead is speech therapy. My friend Rashmi has agreed to work with me on speech recognition over the coming months. I am greatly looking forward to these sessions, which should play a key role in improving my ability to understand speech more naturally.

This marks the beginning of the next phase of my life. I plan to share my progress again after a few months. I’ll end this blog on a happy note, with a picture of me and my guitar — a small but meaningful symbol of how far this journey has already come.

Discover more from graaja.blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Amazing description . As professionals we hardly ever get to hear such detailed descriptions from the CI recipients for our interactions are often short . Thanks so much for the insights. I learnt so much

Thank you Dr. Manoj, for the new life!

May I suggest (or insist) you to watch the movie ‘Perfect Sense’, preferably after attaining maximum spectrum coverage in your listening cognition. Max Richter’s background music works so well and the loss(of something), the recuperations and the joys in persisting to the path so aligns with the theme that repeats in that movie.

Sure. I will definitely watch this movie soon!

Wow coach, so well explained in simple words but with great details. Keep writing and educating us. Thanks for the openness in sharing.

Thank you Prem!

Insightful

Thank you!